“[…] this man who, using time as an instrument of something else, treated it, as an architect, as if it were matter […]”

Renato Pedio

T.E.A.M. research is based on experimentation. The Piattaforma Zero represents the first laboratory in which to test basic dynamic structures, detached from a precise context. In order to both get a better understanding of the phenomena we are studying and to test the tools of our workflow, we felt even the need to confront existing projects of kinetic architecture.

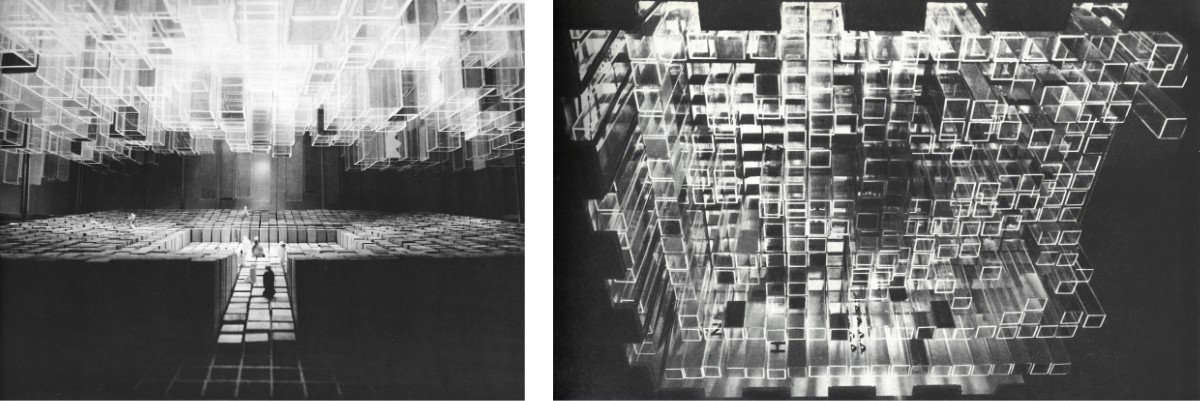

As a first case study we have chosen to deal with an iconic project of recent architectural history: the pavilion for the 1970 World Expo in Osaka by Maurizio Sacripanti. This architecture, unfortunaely never realized, was presented at the competition of ideas held in 1968 to select the building that would represent Italy at the international exhibition.

Sacripanti himself thus summarizes the key characteristic of the project:

“the project proposal is simply to use time as an effective parameter, manipulable in a concrete way – technically as an architectural tool on a par with any other. After that, the path through a built space becomes the path through a combinatorial beam of built spaces, each time new in dimensional values but always constrained within the control of the project: the fourth dimension uses the other three”.

Maurizio Sacripanti (Roman architect, 1916-1996) has always been attracted by the conquest of the fourth dimension suggested by the Cubist and Futurist avant-garde, but above all inspired by abstract art, kinetic art, and programmed art. He personally knew artists and exponents of these currents, with which he had a continuous exchange of ideas and experiences. In the Osaka pavilion, he was able to materialize what he had always pursued, expressing movement both physically and perceptively, going beyond what the architects had designed before. Time is tangible and breathable and technology becomes a medium to bring kinetics into architecture.

The automatic movement of the shapes is processed in an almost mystical way. The evidence can be reached by the meticulous attention that Sacripanti pays to the technological detail, even more than the architectural one. As he wrote, “The architect’s task is to master technology and make it a language” [2], anticipating the themes developed by high-tech architecture in the 1980s. The Osaka pavilion – using the words of Paolo Portoghesi – is a Pantheon set in motion [3].

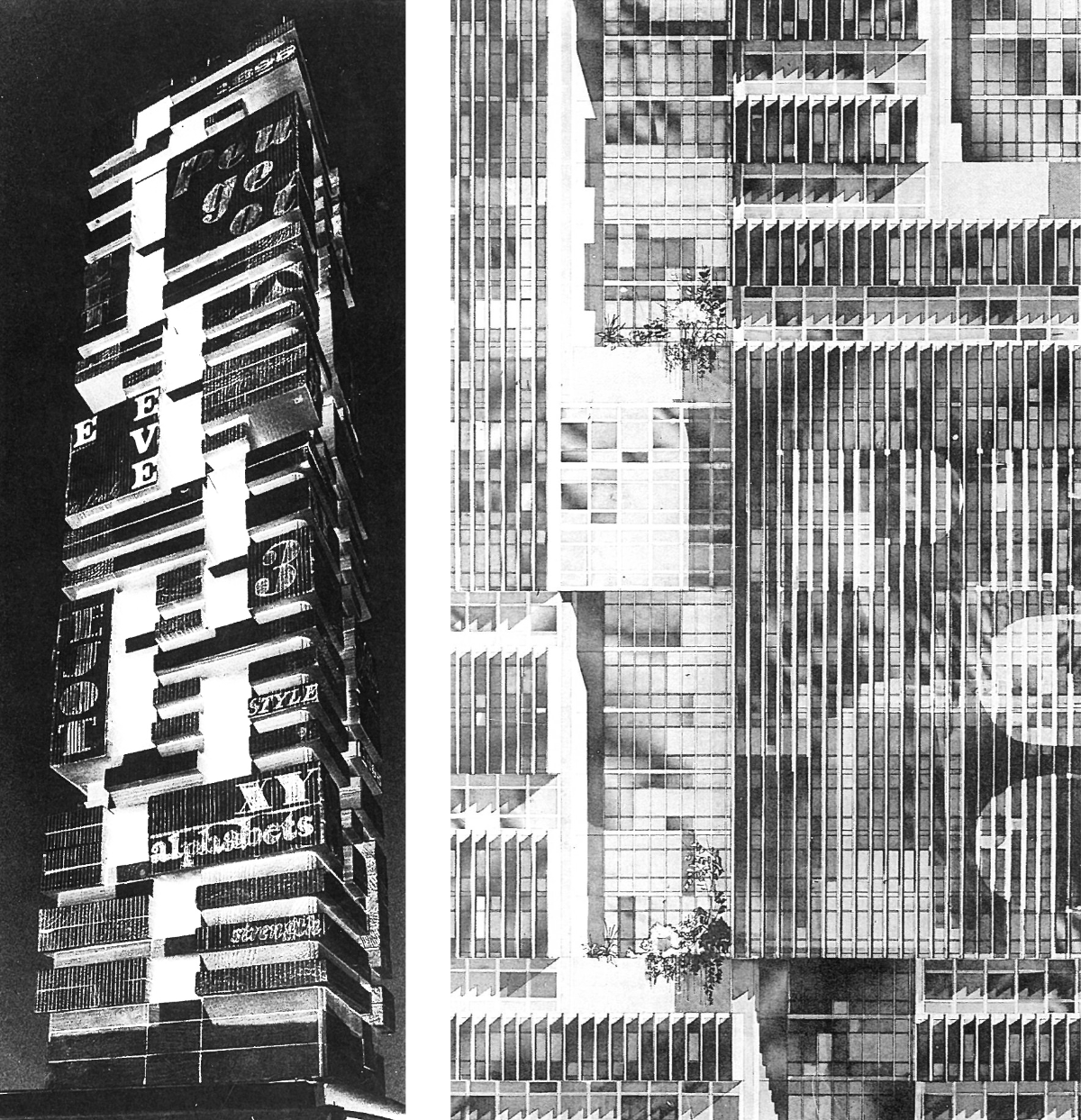

The variable arrangement of the elements that constitute the architectural space is a recurring theme for Sacripanti, who began to explore the dynamics of structures in the early sixties. Examples are the project for the Peugeot Skyscraper in Buenos Aires, consisting of mobile panels for the facade cladding, and the Teatro Lirico in Cagliari, where the floor and ceiling of the theater configure the space through the variability of their movements – he was inspired by the scenic representation of John Cage’s ballets [4].

From the movement of the structures to that of the furnishings, he also ventured into the design of a propulsion closet, able to move in the different rooms of the house according to the actual needs of the user [5].

The kinetic approach brings to Sacripanti’s activity an equally innovative characteristic of his work: the interdisciplinary approach, with which he faced every design challenge. He was a wise conductor, able to get the best from different professionals such as physicists, engineers, artists, writers, draftsmen. Even in his design lessons at Sapienza University, he bought to the classroom the artists he loved in a fruitful and transversal exchange with students.

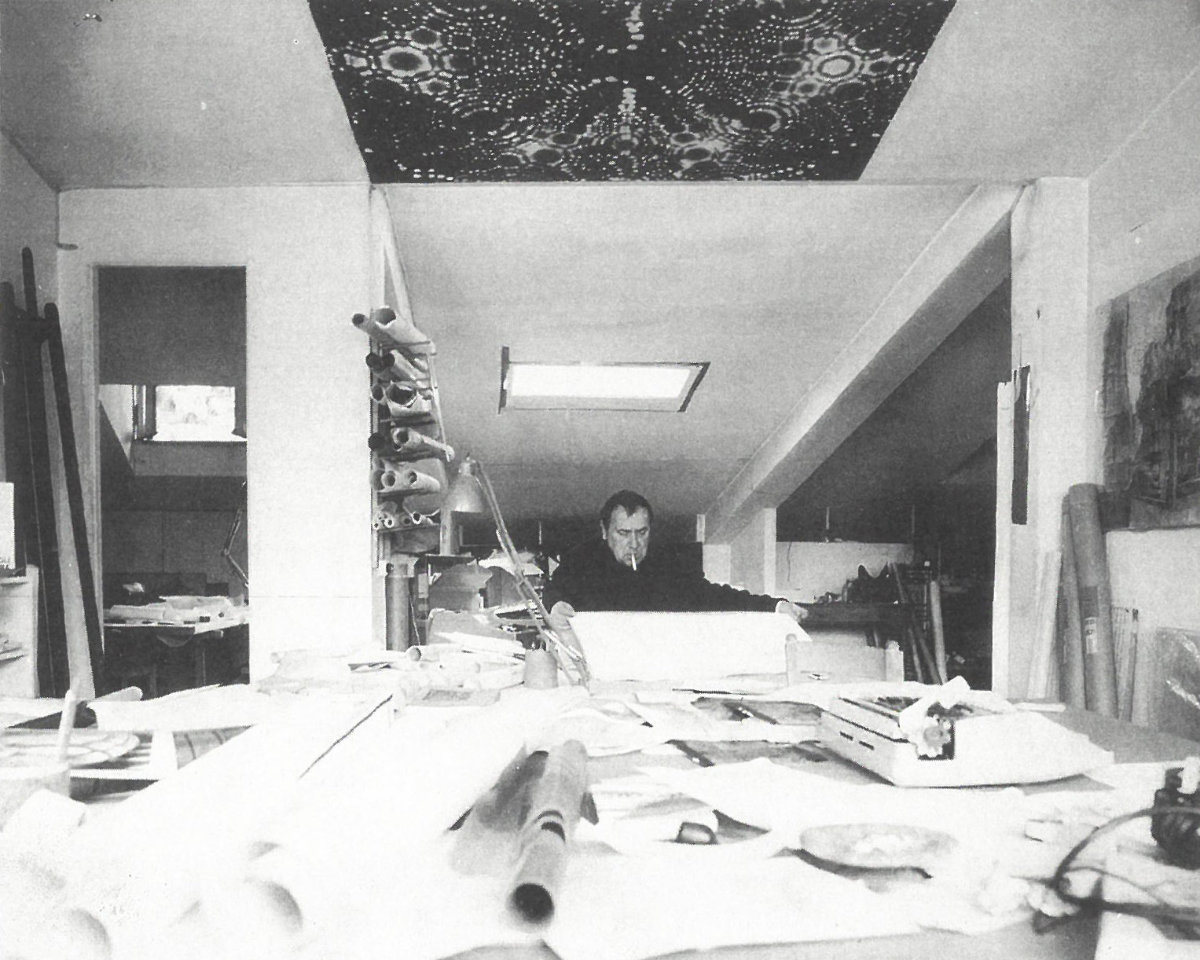

Far from the speculative logic, characteristic of many Italian architects of the period, he was an authentic “outsider” both in the professional and university context. In his studio-workshop full of stimuli, inventions, and visions of the future, the projects continue to live in unpredictability. This trait should be understood as the inability to define a complete picture of his architectures because time and human beings are constantly called to change them. It is impossible to fix in a single frame the multiple aspects of his works. Probably the only way to capture the essence of Sacripanti’s projects is to go through them and experience them.

This is why we were not satisfied with digitally reconstructing in detail the form and mechanics of the Osaka pavilion. We went so far as to create a VR scenario to look at it from within, spectators of a multitude of dynamically balanced spaces in a constantly evolving architectural landscape.

The Osaka pavilion in T.E.A.M. therefore becomes an opportunity to test the digital tools adopted and to experiment with the relationship between kinetic elements and the visitor who travels through space in continuous movement.

Thanks to the interviews made with some members of the original competition team, we designed the architecture down to the technological detail, returning an image as close as possible to the choices made at that moment. The experience in VR is an attempt to connect us with the brilliant mind and architectural approach of Sacripanti, trying to better understand his design intentions: a small tribute to the richness that he has left us.

Our journey about Maurizio Sacripanti and the Osaka experience continues here, with the competition for the Italian pavilion for the Osaka Expo of 1970.

[1] M. Sacripanti, from “Domus”, 473, 1969

[2] Translation by the authors. Original Text: “Compito dell’architetto è impadronirsi della tecnologia e tramutarla in linguaggio”, Neri M. L., Thermes L., Maurizio Sacripanti master of architecture 1916-1996, in “Bollettino della Biblioteca della Facoltà di Architettura dell’Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza, Gangemi Editore, Rome, 1998, p.111

[3] From the lectio magistralis, “Design the mutable. Maurizio Sacripanti 1916-1996” held in 2016 by Paolo Portoghesi (1931), Italian architect, academic and architectural theorist.

[4] “At the last Biennale a Cage ballet was performed with scenes and costumes by Rauschenberg. We went there. Entering we were welcomed by a heretical music, mixed, hanging and rejecting, then it was a new show: no longer the scene with fixed objects, but a ‘non scene’ organized with mobile objects and a language resulting only from the modularity of moving planes, painted bodies of dancers, material images, tapis-roulants….”(M. Sacripanti reported in Giancotti A., Pedio R., Maurizio Sacripanti. Elsewhere, Testo e Immagine Torino 2000, pp. 18).

[5] Extract from the interview with Franco Purini and Laura Thermes, Poplab 2020.

Cover image

Maurizio Sacripanti in his studio at Piazza del Popolo in Rome

From Accademia di San Luca, Maurizio Sacripanti Maestro di Architettura, Edizioni De Luca, Rome, 1997, p.8